The first social media platform was a cardboard box in front of Leopold's Records in Berkeley in the 1970s, and I think about it every day.

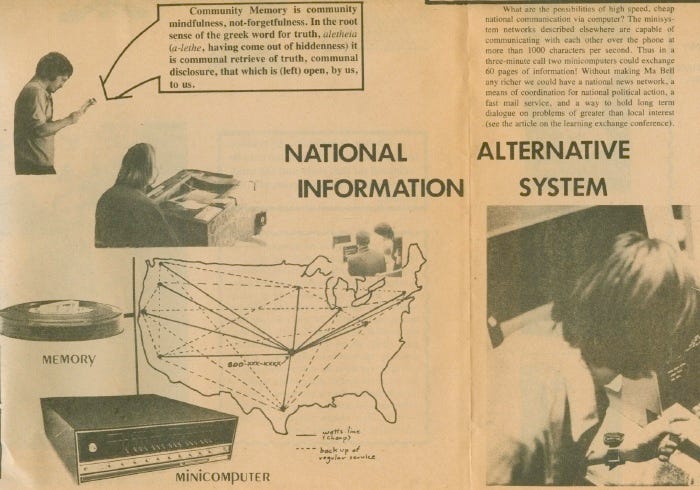

Community Memory was a teleprinter that allowed users to type messages and have them stored on a remote system. It ran on an XDS-940, originally Scientific Data Systems's 940 before Xerox bought it in 1969. It ran on a Berkeley Timesharing System (BTS) as it's operating system.

One thing we have to understand about computers at this time is that even though they were funded and housed in university labs that could afford the resources, they were incredibly inefficient. Your typical programmer would draft a program on a card, send it to the operations team which would run the card to the machine and schedule it to be run in a big queue of other programs. Meanwhile, the programmer sits around waiting for other jobs to run until their program can get through the system. Finally, the program spits out an output, which the ops team then runs back to the programmer. Imagine an Abbott & Costello routine, but in the hallowed halls of Stanford University with lots of sweater vests.

The 940 comes around as a system for the everyday gal. It uses a nifty system called "time-sharing" where the computer's resources are shared in tiny slices of time relegated to different users or programs. It runs a little bit of a program, switches to a new program and runs a little bit of that program, and then cycles through them all over and over again. The constant switching between programs gives the illusion that these processes are happening simultaneously. You can essentially cram in a bunch of work to the same system as long you have the processing power to do the switching.

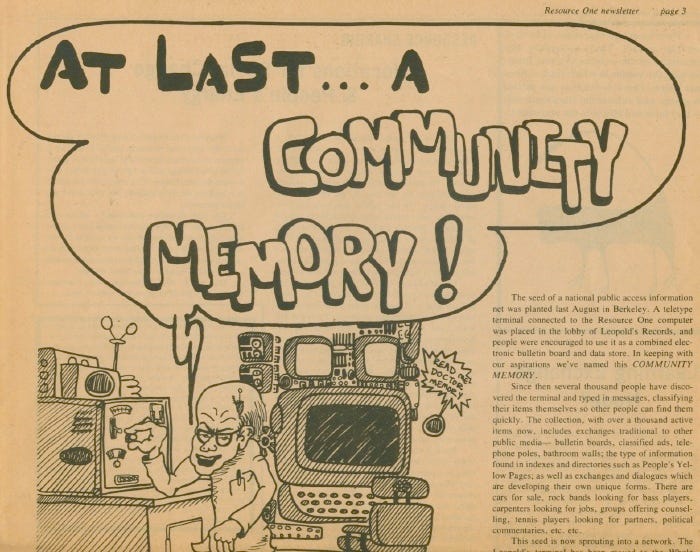

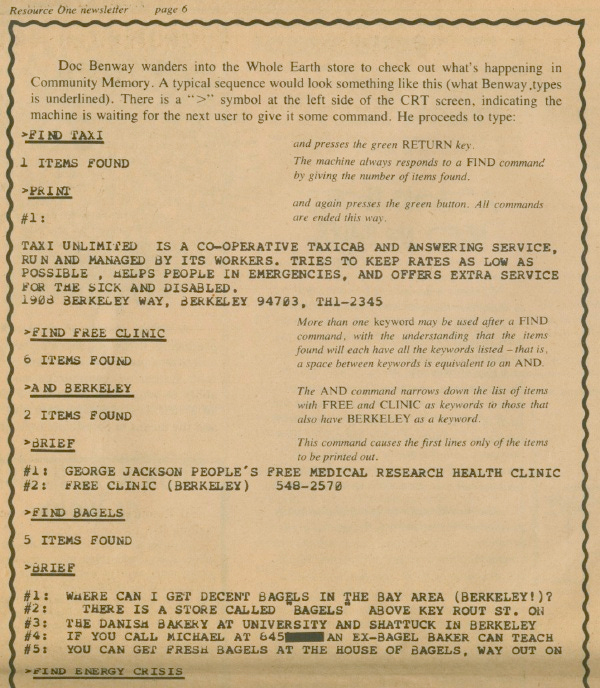

Community Memory capitalized on this functionality by allowing users to type in messages, categorize them with keywords, and store those messages in a retrieval system that other users could then search. It was a modern-day bulletin board; it was searching Craigslist; it was "community mindfulness, not forgetful-ness...it is communal retrieve of truth, communal disclosure, that which is (left) open to us, by us."

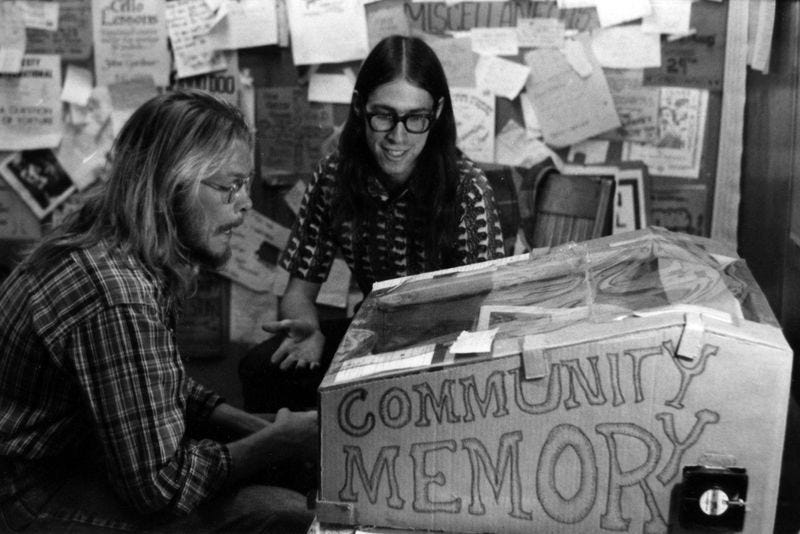

They had to put it in a cardboard box, it was so noisy. It was full of classified ads for bands looking for a drummer (perhaps the oldest problem the internet tried to solve). Poets filed their half-baked lines under "truth" (I don't actually know if they did this, but as a poet myself, this is how I use data structures, so I'm assuming a lot here).

Notably, the creators of Community Memory had pretty liberatory politics, what you could expect for Berekeley at the time but not for folks who would go on to work for IBM. They write in the full-page ad shown above:

We are thus interested in direct contacts, direct information, direct access by people affected by power to information on that power, liberation of power from the constricted grasp of the few to its rightful place as the wealth of the information-sharing community. This involves detailed, precise, valued struggle in a lot of media - money, education, politics, distribution, video, print, speech.

One of the things that's conspicuously missing from histories of computation, and especially in open source, is just how radical the vision of these first programmers was. I was taught that it was "free as in speech, not free as in beer." But Community Memory complicates that premise. It suggests that the creators of Community Memory wanted both unbridled access to information exchange and for it to be free and accessible to the people. They explicitly mention keeping the system as cheap as they can, not giving any more money to Bell Labs.

And they clearly weren't alone in their desire for information liberation. Early in its lifetime, Community Memory had amassed over 1000 messages in its storage bank. These included an ad for a worker-owned cab company, places to find bagels, free clinics, and primers on the energy crisis.

Imagine climbing the stairs to Leopold's, sitting down on the wooden chair with gum stuck to the back, placing your hands in the hole where the keys were and searching across time and space. There you are, surrounded by other explorers, your clunky keystrokes appearing as graphical marks on the terminal screen, like a Victorian magic box. There's a folk musician about to make her break, the corner store clerk sharing his beat fiction, the computer engineer about to be poached from their life of tinkering in the basement, the kid from around the block who searched the ground for enough coin just to be known and to be remembered. All of them leaning into the screen, giggling, pointing, saying, "No, type this" and "No, put that." The Allman Brothers are playing in the background. I am not born yet but my father is 11 years old somewhere in the Everglades, dreaming about the TARDIS's back-end architecture and ARPANET, about a home he will never have but will have to build. Everyone leans into the screen, marveling at what we can know about another person.

Lee Felsenstein, one of the fathers of the personal computer, said about Community Memory that it, "opened the door to to cyberspace and found it to be hospitable territory." For those of us who grew up in the 1990s, we have some semblance of this experience with the network: Internet Relay Chat was where many of us found our fellow Nirvana-heads across the world. It was where we played out young love on AIM with our crushes we were too shy to look in the eye at school. It was where we learned markup just to spice up our away messages and build our avatars. Oh, when we learned how to embed media! The copyright industry could never, we were copyleft all the way.

We owned the means of production of the world wide web; we had our own Community Memories, housed not in a cardboard box in front of the record store but in our libraries, living rooms, and maybe even internet cafes. It was Felsenstein's dream come true, a community mindfulness that came to us in the form of doll makers and geocities sites dedicated to our pets.

I think we all have a sense of when the web changed. We might not agree on the exact year or decade, but we typically point to the advent of social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter as the shift away from what Community Memory represented and towards a commodity economy of our knowledge and identities. At times, I have wondered if I just grew up and out of the internet, and that's just what happens. But the shift from largely one-way communications to participatory platforms did something to us culturally. To quote the creators of Community Memory, the network became a space we went to forget.

I think a lot about Community Memory, I spend an hour at the library billboard, I scour the Internet Archive. I feel safe in the black-on-white text. I feel connected to the slips of paper offering to watch my dog. I think about the computers I've loved all my life: the little Apple II I called the pooter. Simone Giertz's lipstick robot. Even the record player is a lovable archive, transforming the ridges of a physical medium into dancing (an etching that, by the way, couldn't be erased as the media transformed into shinier, glassier blu-ray and CDs - you have to crack them little shits to get rid of every trace).

In memory of Community Memory, in memory of the traces those adolescents of the world wide web left. In memory of the huddle around the screen, the leaning in.

Have never wanted to time travel more than I did after reading this, thank you for sharing I’m glad I came across you! (I guess that’s one beauty of the modern day social network, though those are few and far between)