I've been thinking about zines again. their textures, their stories. the quiet places they carve out for authenticity. the places they are made: in bedrooms, in cafes and makerspaces, and since the late oughts/early 2010s, the internet. the way they are shared: in a Kinkos copy center, left on the seats of the #6 bus going north to downtown Chicago, in the library, and in the bookshelves of queers and weirdos across America.

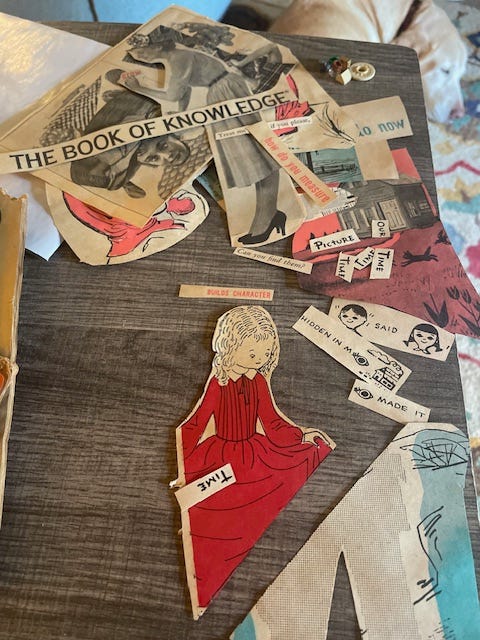

last week I started making a zine for the first time since I quit teaching. it's been about 3 years since I opened up a glue stick. I've been collecting ephemera from the Scrap Exchange and antique stores around my hometown, looking for vintage postcards, stickers, and thrown away art that might end up as the background to a spread or the pieces of a poem. these scraps have piled up in my tiny office, the background to my conference calls at work cluttered with the hope that one day I'll make something out of all the trash I'm collecting.

something about these days makes it impossible to string two sentences together, so I've leaned into the disjointed way zines call us to make meaning out of raw materials. they've always helped me in this regard: I've given workshops on zines, zine history, and zine-making (you can find an example here). in the classroom, I used it as a tool for students to generate ideas about their papers and the things they wanted to say about the world. I used to work in a university makerspace and led workshops on how the history of making was built on the principles of zines. I made a zine to help me study for my comprehensive exams, which included a history of technology from pre-industrial craft communities to tractors to the young internet.

a younger me used them to make sense of many things: my changing neurochemistry, abuse, the queer nature of pine barrens, and what it meant to leave home. I would collect detritus I came across in my daily walks, sit down at night with my scissors and tape, and just stick shit together haphazardly. in high school, I typed out my poems on my olive drab Smith Corona and stuck them to backdrops I had created from trash, cigarette butts, magazine cutouts, blocks of text I photocopied at the library, and sometimes my own doodles (I was never a good drawer or painter, but zines were always a place I didn't have to care whether it was good).

one of my favorite zines - regrettably one of the only ones I saved the originals from - was to my best friend on their birthday while we were both away at college. I made erasures of the letters they used to send me, superimposed their face onto scenes from my Irish language textbook's creepy illustrations. there were poems, stories, observations of my new life in Chicago, and screenshots from the 1995 BBC Masterpiece Theater mini-series, Pride and Prejudice, starring my celebrity crush Colin Firth. I was an amateur film photographer so many of the backgrounds were original prints that reminded me of our treks along the marshes, swimming at night in the oyster beds, or the fields of golden reeds we would run through after school let out. the three-dimensional pages filled with flowers and used tea bags and bits of things I had picked up, far away from my home and my friend and my bedroom. this zine accumulated itself. it grew from flat to full.

I've been thinking about zines for a couple reasons: one, I have gone through a multi-year period where I haven't written anything creative. I work in technical marketing, so I do write - I'm regularly drafting instructional docs, marketing materials, and other genres that matter insofar as their final product looks and sounds like someone else. this isn't a bad thing; it makes me happy and busy and pays the bills. but something about the practice has a kind of film over top, a separation of my write-ing self and my writt-en self. so much of our production of thought and language involves using tools that are meant to hide the transparency and messiness that are inherent in sticking ideas together. but a zine starts with nothing; no blueprint, no pre-determined point, no finality. no expectation of a final product. it is all cutting and arranging. it lays bare how all forms of art, from language to architecture, are built from the ground up, not designed from the head down.

the other reason is that there's been a resurgence of both the aesthetics of the early internet and the creation of zines over the last year or two, on substack and elsewhere. I see so many wonderful thinkpieces about people making zines, thinking about zines, loving zines, wanting more zines in their lives (see some of my favs below). in equal amounts, my feed is full of treatises on the artistry and comfort of the tomagotchi, dollmakers, and Clarissa Explains It All's transparent telephone.

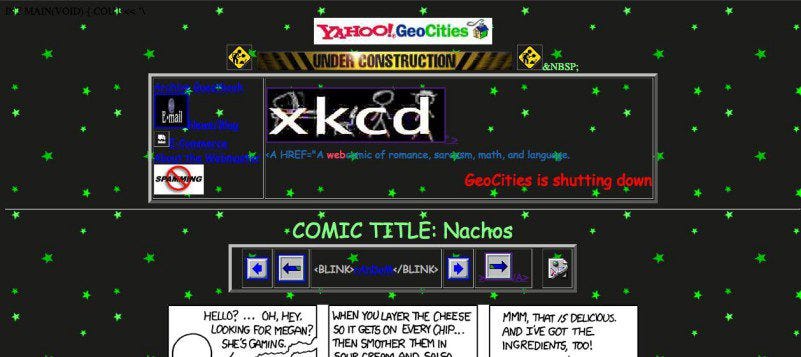

this is not a coincidence. zines were in their hey-day in the years the social internet as we know it was first surfacing. the ways we built our little personal corners of the world wide web with the building blocks of FTP and HTML were the same logics of assemblage that we used to make zines. prior to the early 2000s, you could not participate in the internet without the physical tools and pieces of computation, but these tools were accessible and even taught as explicit skills needed to engage in global discourse, as easy to find as scissors and glue. the minimum requirements for setting up an online space were a low bar to clear, unlike today where you would have to have a complex understanding of Javascript, HTML, and CSS to even spin up a website. the young internet allowed us to turn things inside out in order to make them.

one of the frameworks I use to think about zines was something called bricolage - the way meaning arises from disparate things pieced together (related concepts are Foucault’s heterotopia and Deleuze and Guattari’s agencement). these theories were being written in the late 80s into the mid-2000s, and again, this was not a coincidence. this era of social communication was defined by sticking things together and placing a transparency over the mechanisms of thought - not just what we wanted to say, but how we came to say it.

if we think more about the timing of zine culture and the early internet, one could easily argue it was a response to the hyper-capitalism and austerity measures of the 1980s culture wars in US politics. and one would be right in seeing similar political dynamics arising today, perhaps why young Millennials and Gen Z are so fascinated by both. we are seeing the result of almost a decade of corporate consolidation of communication platforms, alongside a steep rise in authoritarian politics.

beginning in the mid-2000s, social media as a distribution mechanism saw significant changes. website makers like WordPress, Wix, and Squarespace were born amidst an era of shrouding: we went from the gooey interiors of iMacs to the slim opaque LCD screens that pervade our technical landscapes today (for more on this, I highly suggest Kirk Gordon's essay on transparency and technology). our earliest social internet required an orientation to scrapping, both in the physical sense of cutting and pasting and in the social-emotional sense of being scrappy. even early social media like Xanga, Yahoo geocities, LiveJournal - these were based off of a combined diaristic and bulletin-board aesthetic that meant what you created was your own. the earliest networked places for the distribution of ourselves and our thoughts looked like zines.

but the rise of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube shifted the locus of making from the user to the corporation. these platforms made things easier by placing the tools of production behind closed doors and handing WYSIWG (what you see is what you get) editors over to creators as a simulacrum of the raw materials they once had access to. they changed us from producers of the internet to consumers of the internet, and of each other.

so we gave up our tools. we've gotten out of practice. the filminess of our current technologies - the flat iPhone screen, the ready-made production built into the TikTok application - means that we have less and less ability to distribute ourselves in authentic ways. the means of communication are much more complex than they used to be, too. the technical skill needed to produce thought requires a bachelor's in computer science, not a library card and a glue stick.

this is also not a coincidence: the rise of authoritarianism calls us back to ourselves. Foucault famously and hilariously told us that everything is a prison, and here we are, seemingly unable to escape the enshittification of the only way we have to communicate who we are. we are tired of things being so hazy. we are tired of being detached from our own selves and our own process, our own tools of connection. I think zines and the early internet are making a comeback precisely because we see a need for being both undercover and laid bare.

I guess what I want to say about zines, because it’s actually quite difficult to write about them because they are everything and nothing all at the same time, is that you should make a zine. you should make a zine because a zine doesn’t care if you’re perfect, but Instagram does. you should make a zine because to be vulnerable is an act of resistance. you should make a zine because it is the closest you can come to the complex circuits that you’re made of.

YES YES YES we should all be making zines and chaos websites and webrings and all of the other things that allow us to show up as the gloriously messy humans we are without interference from the algo or the corporation. I'm happy to see this shift because it's not about walking away from something, it's walking toward ourselves and real connection.

I love this soooo much! From one Zine Krys to another, let's make a covenant to always ZINE IT!