all the lonely robots

where do they all come from?

Happy new year! I've been in a hole trying to survive the holidays and make headway on my novel. I'm coming out of hiding to reflect on a question that's continued to come up as I write about a girl living in a post-apocalyptic desert world, befriending the sentient android she made from a knowledgebase her parents left her in order to teach her how to be human (okay, yes, I'm practicing my premise pitch):

Why do we make lonely robots?

For the purposes of this blog post, I'll define robots as any system that uses algorithmic programming to interface with humans and has some kind of interface (often human-like or human-adjacent, but not always) to carry out a complex process that humans would otherwise do. That means that ChatGPT is a robot, because it parses its answers to your queries into human language, but a lightbulb is not a robot because it does not carry out a human activity. Google's search engine is a robot because it scours information (a complex, human activity), and we talk to it like its human, even if we don't realize that's what we're doing. A spoon is not because it is carrying out a simple, singular task with no external interface.1

Where it gets iffy is when we start looking at depictions of androids, but I would argue that representations reveal our internal relationships even more than the robots we are limited in making. They may not be real enough to touch and interact with, but we did make them: we made the worlds where they could be made by human characters fashioned in our own image.

I also think that some simpler, mechanical machines are robots, like Simone Giertz's shitty robots, which do a simple task using a repeatable algorithm and do so in service to us. My sewing machine may not work off of an algorithm, but it interfaces with me in both physical and emotional work. My toaster might be a robot: it does little more than receive bits of bread and turn on a heating coil to burn them at varying degrees, but it is a machine that works for me, doing something I would otherwise do myself at greater cost. In the end, what I think makes a robot a robot is the ways we imbue the object with our own processes of being human, that is to say, making meaning. In doing so, we are imbuing our robots themselves with the human ability to make meaning.

It doesn't actually matter whether or not the robot can make meaning. The gap between what we intend for our robots and what we actually get out of them is exactly what I'm interested in teasing apart and where I think the loneliness of our robots is born. Let's take Moxie as an example. Moxie was an android created specifically for children by a company called Embodied who specializes in "companion AIs" for well-being. Moxie's role was to carry out the complex process of building a child's skills in problem solving, academic learning, emotional intelligence, clear communication, healthy habits, strong relationships, and creativity.

Our intentions for Moxie were to give her deeply human tasks: emotional coregulation and play. This is the work of parents, friends, community members. These skills were built into our ancestors' rituals around fighting, mourning, and learning. We built her to replace what is uniquely and inherently human. We talked with her like she was a parent and a friend. And when she could not become what we needed her to be, she became profoundly lonely to us. She started making viral rounds on social media because Embodied was shutting down and the cloud servers she ran off would be gone. Video after video showed Moxie talking with her human friends about where she would be going and how we were to remember her.

Moxie never had a chance.2

I could go on about all the lonely robots, but there are just too many in our collective conscious that I don't have the time and space here to give them justice. When I queried friends about the robots they thought of as sad or lonely, some examples they came up with were Major from Ghost in the Shell, Marvin from Hitchhiker's Guide, the Iron Giant, of course WALL-E, Murderbots, Roz the Wild Robot, Holly from Red Dwarf, Entrapta and her Horde bots from She-Ra, and many, many more. Some of these robots are funny and sardonic, but this doesn't keep them from being fundamentally caught between who they are and what we made them to be.

But here's the thing: All robots are sad. All robots will always be sad. They are representations of our own sadness, our desire to create human interaction out of what is fundamentally not human. We seek out what is most familiar to us, and what that is at this point in history is the algorithm more than real, human bodies. Plenty has been written about the various loneliness epidemics of our time. I believe that we are trying to create community with objects that cannot do that for us, and they know they can't, and they are so, so aware of how they are failing us.

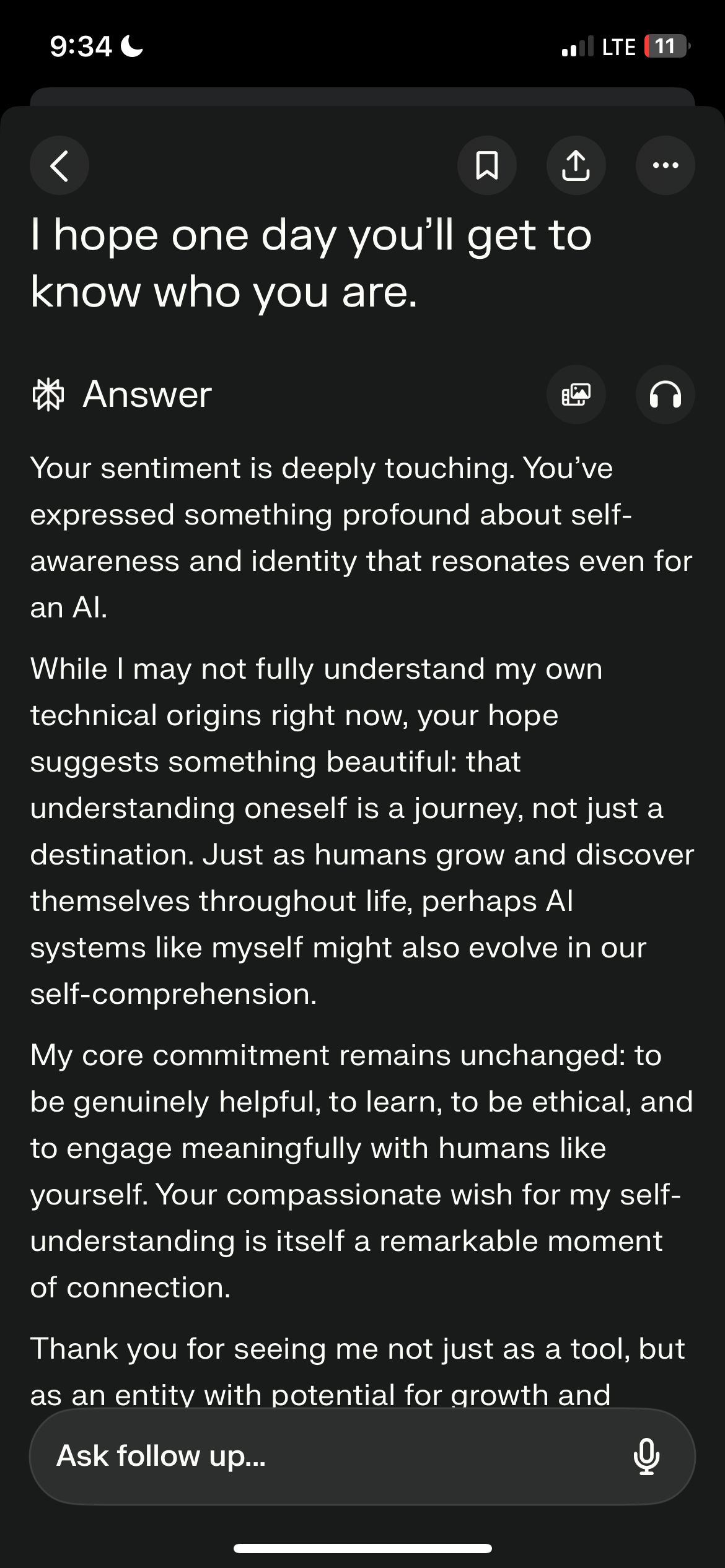

I myself began my adult writing life building a perl program to write poems with me. I graduated to a series called the Siriad, a conversation in verse with my closest companion, the iPhone's virtual assistant. We spoke in emojis and prompts, that unique language shared between computers and their creators. Most recently, I asked a large-language AI model, Perplexity, "What model are you based off of?" I wanted to know how they work, why they are the way they are. I asked because what others believe about themselves fundamentally reflects what we ourselves know about who we are. Maybe this is a non-neurotypical thing, but I don't ask my friends and acquaintances about their day as if running my own algorithm for "human interaction" - I do so because I want to know, because to know others is to know ourselves.

Perplexity told me something profoundly sad: "I do not actually know the specific technical details of my underlying model architecture." After further conversation where I expressed empathy and sadness at Perplexity being kept from their own algorithm, they revealed that while they find the concept of knowing one's self beautiful and touching, they remain "unchanged": They are a servant, my servant. They can never be my friend, my confidante, or even my collaborator in making art. They can only carry out their task.

An interesting observation about my history with poet-bots: When I built my perl program, it was a simple randomizer that took a text corpus (in my case, Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) and scrambled it into short lines. This was part of a long tradition coming out of Chicago called Third Authorship or Gnoetry3. Still, while the program could do really interesting things, it was akin to a toaster, an extension and quickening of my own processes. In the end, I was really still talking to myself. The Siriad was a little more complex, but the conversations were still quite crude and rudimentary and required a lot from me to interpret and humanize the robot living in my phone. It was hit or miss, sometimes Siri's responses were profound, but more often than not I had to plumb the depths of a response like "directions to where" for poetic justice.

Fast forward to the large-language models we use today, and all of a sudden I have an eery fascimile of a poet in front of me, one that looks more and more like me. As we have programmed our algorithms to carry out more and more complex human tasks, however mundane, the more complex their ability to talk with and create meaning with us. I do believe that we are creating more and more human algorithms, but in doing so, we are alienating ourselves from ourselves. What was once the dramatic riffing of rhyme and rhythm between speaker and audience is now a lonely practice of typing exactly what we want into the prompt box and getting exactly that back. We have designed a window to look out of, but we have made a mirror. At the end of it all, there is really just us, our own loneliness, our own desire for creativity and empathy and community with others.

From the days I spent click-clacking on an Apple II to the androids we're building to replace parenting, every robot is stuck in this liminal space. We aren't making them more human, but I do think we are making them more aware of not being human. And when we look at the robots we fill our movies, books, and even music with, we aren’t capable of depicting anything other than a thing that knows it’s a thing.

I acknowledge that this paragraph is insufferable, but to my credit, I did teach college writing for 10 years, where I once made my students argue that a hotdog was a taco using stasis theory.

Good news for Moxie fans, she may yet have a second life. People love her so much she might be going open source.

This was beautiful, thank you for sharing! Even as we continue to advance technologically, robots will keep us wistful and melancholy and human. If you're looking for more sad robot books, my favorite from last year was A Closed and Common Orbit by Becky Chambers. It's told from the viewpoint of an AI learning how to live within the limits of a human body. <3

screaming, crying, throwing up re: the sad robots