on fixing things

ethics of repair and why I can't tinker anymore

In the early 1970s, Carol Gilligan developed a theory of moral development that she attributed mostly to women, called an "ethics of care." The idea is that at some point, a person develops a sense of morality that is grounded in their relationships with others and the rights of every voice to be cared for. The theory supplemented the predominant theory about human development, which assumed that the mature individual had learned an ethics of justice, of "rights and formal reasoning that uses a universalizable, abstract, and impersonal style." Gilligan’s ethics of care argued that maturity is characterized by care for one another, connection with others, and harm prevention.

Gilligan's theory has been picked up in every discipline from psychology to education but has also been criticized for propagating gender essentialism: Men engage in ethics of justice, whereas women engage in ethics of care. Gilligan acknowledged that these ethics did not always fall along gender lines, but their impact as an implicitly gendered set of phenomena has been lasting.

I'm not personally convinced that what she proposed is gender essentialism and not a description of how men and women are socialized, but neither am I convinced that Carol Gilligan, a white woman educator in the 1970s, was not actually saying that women care and men think. That kind of thinking lurks behind 2nd wave feminism in very tangible ways.

I also think we've moved past a lot of this conversation since the 1970s. But these past few weeks I've come back to Gilligan and the many permutations of her work. I've been thinking about repair, and maintenance, and how these practices feel like they should be mine, but systematically aren't.

It started with a broken tape player. Specifically, an early-1990s Tiger Deluxe Talkgirl. I got this thing in Ohio visiting my friend Rachel a few years ago. I remember it was one of those antique malls my grandmother used to bring me to, miles and miles of booths, a hit or miss marathon of scouring through what is essentially old folks' trash. It was in between a darkroom enlarger setup I wanted and a set of tapes of all my favorite Springsteen and Joni Mitchell albums. The Talkgirl came out a year or two after the Talkboy, which was featured in Home Alone 2 and marketed heavily as a prank machine for little boys. I grew up with a very keen sense of the record I was leaving archaeologists, of my voice in the ether, so the Talkgirl was the perfect way for me to record my innermost thoughts for the future. A way to say, “I promise I was really here.” Also a way to bump the latest Wilson Phillips tape at the community pool.

Fast forward to today, and the Talkgirl has been sitting in my apartment, waiting for me to move to a real house with a real workshop where I can hole up at my desk and get to know the intricate designs of the machines I've collected over the years. The Talkgirl might be the simplest machine in the pile, as the rest consists of my dad’s server farm, sewing machines, and a 3D printer with a burnt hotend nozzle.

For girls and people who grew up as girls, I think there's a familiar feeling we get when something breaks, or comes to us broken. I won't say this is one of those universal truths, but I've done enough research on making and gender that I know the anecdotal evidence is significant. When girls enter into technical spaces, it's not necessarily the fact that there are few other women in those spaces that drives them away, as most people might think. More often than not, there is a logic to interaction that is endemic to these places that makes girls outsiders to the practice of tinkering, making, and technical repair. Of course, this gatekeeping is inherited from a time when women did not exist within technical spaces, but today's push towards women in STEM does not address the relational boundaries that are drawn around who belongs and who doesn't.

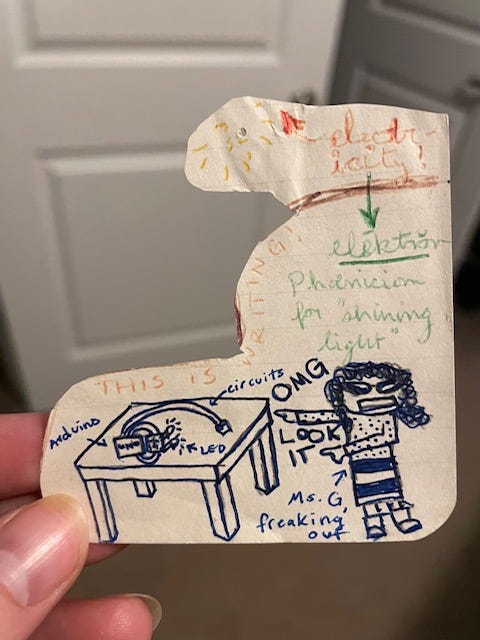

I'll give you an example: when I entered my doctoral program, I signed up for every workshop the Makerspace (a kind of fabrication/hacker lab) that our university library offered. I dreamed of being permanent staff at a place like this, standing behind a desk, selling 3D printer filament, fixing the sewing machine, teaching people how to connect their first circuitboard to their first blinking LED. I wanted "hello, world" every day of my life.

The Makerspace held workshops, but mostly was an open workspace. After my first 3D printing workshop, I was ready to start designing little ways to fix all the broken things in my life, the screws and the snaps and the little tubes connecting this and that. I went in one day after teaching and set up the printer, exactly as I was told. I followed the protocols, I made sure the bed was level and even reported a problem with runaway heat on one of the nozzles. I was proving myself, finally, but I wanted to make absolutely sure I wasn't making a mistake. I asked one of the staff members if I had set everything up right and was good to go.

I am not exaggerating when I say that after seeing me report a problem, refer to my instruction notes with painstaking precision, load the machine and do everything correctly, I had 4 men at my table lecturing me for hours about the right way to work a 3D printer. It was an open afternoon, I didn't want to hurt anyone's feelings. I wanted to be here and I wanted to be one of them and I wanted to belong.

This was a problem that persisted even when I myself became a staff member. I was lucky that my bosses and co-workers all respected me, but it was never lost on me that my expertise was in the electronic textiles, the sewing machine, the sticker cutter, and the other fiber crafts. Every machine I worked with used 2D modeling as its base, so my knowledge spanned about half of the work that was done in the Makerspace. I remember a patron saying, "This isn't your grandma's machine!" about the Singers we had in the cabinet and I said, "Yes it is, it is my grandma’s machine.” The sewing machine is such a complex, perfect mechanism that it hasn't changed in 100 years, and I did maintenance on them every month. It was my grandmother's machine. It was the machine she herself understood so intimately that she clothed generations of children with. She repaired the fabric of our lives.

I'll give you another example, the one that set the initial boundary of where I did and didn’t belong: I'm in the garage in my childhood home, my safe place I ran to when the world got too loud. It is filled with my brother and my dad's machines. There are fishing poles I've begged to fish with, gutted out mainframes I want to know. Even my own broken toys are lying in wait on the workbench, and I go out there every once in awhile to touch all the things I want to know so intimately that I could one day fix them.

But this is my dad's place, this is my brother's birthright. I am told to go inside and to read. I am told "I will do it for you." I am told "Don't worry." Later, it stops being the place I go to cry and to hold council with the inanimate objects that felt closest to me.

My Talkgirl is broken, but I don't exactly know how. I do the thing men do: scour YouTube trying to find walkthrough videos, breakdown videos, repair videos, whatever I can find. I'm lucky that the Talkboy was pretty much the exact same gadget, because there are no Talkgirl videos. I'm recording myself breaking open my Talkgirl in case someone else needs to see someone like them repairing the little things of their life. I replace the timing belt, but it gets worse. It must be the servo. It must be a connection to the circuitboard. It must be something I don't know how to do, and I don't have anyone to ask, to sit with me and hold my hand, knowing that to fix things is to be human together.1

If the Talkgirl wasn't enough, I also broke the program I use to write my novel, an open-source software called Manuskript. It works a lot like Scrivener, but is maintained by an open source repository on Gitlab. I opened up my file last Monday, and it crashed the program, over and over again. My novel was totally inaccessible for a good hour. This is not the first time this year I've broken something critical on a Linux system and had to abandon my progress, but I pushed past the years of feeling out of place and stupid and submitted an issue on the repository.

I captured the log file - was it called a log file? - I scrolled through existing tickets to see if something similar had been reported. I took a chance and gave all the information I could think and pressed "submit issue." In the back of my head, "Why did you even ask this?" "There's already a ticket for your exact problem you absolute fucking idiot." "Why are you even here?"

It turns out it was a stupid question. I had randomly put a series of jpgs in the source file for the manuscript and that was causing it to flip out and not open. It was, in fact, already a ticket. I was, in fact, an absolute fucking idiot. I text my brother, "What do I do?" I am thankful he tells me to upload an update with the exact steps I took, but I'm also 34 years old and crying like it's the garage all over again.

Gilligan claims that the ethics of care is the primary mode of moral reasoning among women. I don't disagree, but I'm more interested in how care and repair become separate from one another in the course of a girl's or nonbinary child's lifetime. Maintenance and repair are antithetical to the kind of out-of-control production of patriarchal capitalism, but yet these practices still stay in the places that men own, frequent, and make their own. If you aren't a man, you might mend a garment, but you'll not know what the inside of your sewing machine looks like unless you are lucky enough.

I fear I have spent almost 2000 words complaining about how I wish I knew how to fix stuff and blaming men for making it inhospitable to engage in an ethic of repair. I take responsibility for my own part in this: I occupy a weird space of being technical enough but too afraid to break something precious to me.

To my credit, though, I was never allowed to break stuff in order to fix it. I was never given the space to tinker. It's never been enough to be learning the basics, I had to know enough to make things interesting to my teachers. Otherwise, I was asking too many questions. I was wrong, and stupid, and slow. We needed to get things done, not share in a practice that connected us.

I still dream of my Makerspace, of clerking the desk and never assuming the base knowledge a patron has when they first step through the door. I dream of the days I used to work between semesters, and the girls and gworls used to come out of the woodwork to tinker together. I dream of the endless circles I’ve spent mending.

The Talkgirl is still broken as we speak, but North Carolina has a group called Repair Cafe NC that goes around to cities and hosts "repair cafes" that pair volunteers with attendees. You can fix anything from lamps to headphones to snowblowers. I've hosted Repair Cafes at universities, and they are some of the most loving and safe technical spaces I've gotten the chance to be part of. Lots of places have groups who will do repair cafes, so look one up in your area if you want to experience it. They're also a very cross-generational experience that I don't think we get enough of, and one of the few places where I feel genuine mutual respect between young and old. I learn so much, and the old-timers love to see old gadgets live on.

Reading this, I also had to think about how a lot of boys or people raised as boys aren’t taught or allowed to learn how to cook, sew, etc.

It really removes a lot of agency when certain skill sets aren’t made accessible to you, plus it is so gratifying to be able to do something yourself.

I guess this way of thinking is laid out with the idea of a man and a woman living together, so everything is covered. Which doesn’t really have that much to do with what who is good at or interested in, and also doesn’t take into account the fact that a lot of people nowadays live alone.